This coronavirus is novel not only for its first appearance in humans but also for the impact it stands to have on the world economy. The threat is unprecedented and the ultimate toll uncertain.

The unfolding calamity is at turns similar to the financial crisis, marked by market dislocation; the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, which affected consumer behavior; and adverse weather events like the polar vortex in 2019 that kept swaths of people home-bound and visibly dented economic growth.

Predicting the impact has been a real bear (pardon the reference). China’s data aren’t trustworthy. Italy has only just begun to come to terms with the impact. Limited testing in the U.S. isn’t accurately measuring the spread. Just three weeks ago, the consensus mood was of modest concern, at least as far as the domestic economic impact.

Read More

“Within a very short period of time, the world has become obsessed with the coronavirus,” says David Kelly, chief global strategist at J.P. Morgan Funds. “Even since Monday, I’ve become substantially more pessimistic,” he said on Friday morning, adding that a recession now seems inevitable.

Yet the piecemeal response across the U.S. and the still-developing fallout mean it’s futile to compare this to any prior economic shock or other country’s response. After all, the U.S. isn’t China, with an authoritarian government that can seal off cities, or Italy, with its far smaller economy.

What we do know is that reported cases—even if underrepresenting the problem—are ballooning, prompting school closures, canceled events, and social distancing. Leaders across the country have put restrictions on public gatherings—shutting down sporting events, closing Broadway theaters, and limiting capacity at some restaurants and bars. President Donald Trump banned travel to and from Europe, the NCAA canceled the March Madness college basketball tournament, Austin nixed its annual SXSW conference, and the National Basketball Association suspended its season. The list goes on.

Such measures, though they may help limit the spread of the virus and prevent a protracted recession or slowdown, will no doubt hurt the domestic economy in the near term. Cancelled events mean that consumers aren’t traveling, buying food and drinks, staying in hotels, or just generally spending money. They also mean that companies might not need to be fully staffed, putting some Americans’ paychecks in doubt.

Economists, racing to keep up with developments and adjust their models, are split on whether the shock pushes the U.S. economy into recession. In The Wall Street Journal’s latest poll of economists, conducted on March 6-10, 49% said they see a recession in the next year, up from 26% a month ago. Bond and oil markets are flashing recession warnings, and betting markets reflect rising recession odds.

Whether the U.S. tips into recession depends on whether activity does in fact turn negative in the second quarter and whether it snaps back in the third quarter since a recession is defined by two consecutive quarters of negative growth. For economists at Barclays, contraction in the second and third quarters is the worst-case scenario, followed by a recovery thereafter.

“Within a very short period of time, the world has become obsessed with the coronavirus. Even since Monday, I’ve become substantially more pessimistic. ”

— David Kelly, chief global strategist at J.P. Morgan Funds

J.P. Morgan’s Kelly, meanwhile, now sees at least a 25% drop in restaurant sales and a 60% to 70% decline in hotels and airline revenue, which, added to other declines, will take five percentage points off second-quarter gross domestic product and two points off third quarter GDP before growth resumes in the fourth quarter.

Reflecting the wide variance in GDP predictions, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is forecasting 1.1% second-quarter growth with its real-time Nowcast as of Friday.

Some of the market panic seems to be rooted in fears that the U.S. will impose quarantines and virtual shut-downs as in China and Italy. But while certain municipalities are taking steps to limit contagion, capping crowds at 250 is a far cry from the lockdowns China and Italy have enforced. And given the political realities in the U.S. (it’s an election year), any national shutdown seems unlikely.

As markets hope for some sort of fiscal response, some companies have tried to soften the blow to their workers. Starbucks says it would pay its U.S. workers during a 14-day quarantine required by exposure to the virus; McDonald’s, that it would pay certain employees if they need to be quarantined; and Darden, owner of Olive Garden and other restaurant chains, that it’s working to provide paid sick leave to some 180,000 hourly workers. It remains to be seen how far responses by Corporate America will go to help mitigate the outbreak’s impact.

A hit from the virus hasn’t really shown up in the data yet; initial jobless claims, the best high frequency gauge for measuring the impact, fell in the most recent week, a reminder that it is too soon to predict the extent of the outbreak’s impact. Consumer confidence as measured by the University of Michigan through March 11 slipped but remains close to record highs.

At this point, investors should also remember that not every severe market downturn coincides with a recession. LPL Financial looked at 15 bear markets going back to 1946, excluding the one established this past week, and found that recessions have accompanied seven of those bear markets. (The degree of market declines didn’t correspond with whether a recession happened.)

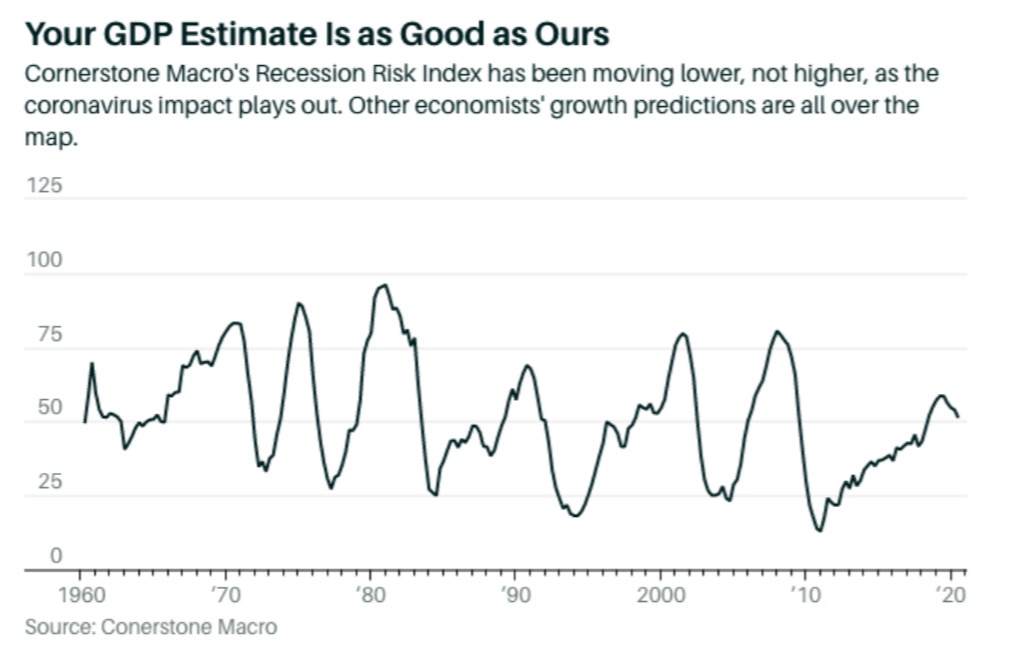

Another bit of perspective: Half of the economists in the WSJ survey are still not predicting a recession. Nancy Lazar at Cornerstone Macro is one of them, and she and her team say their own Recession Risk Index is actually moving lower, not higher.

“Recession odds are falling, as U.S. energy prices, mortgage rates, and global bond yields decline,” Lazar says. She says some of the index’s inputs do call for a recession, including the yield curve and corporate profit margins, and she notes that Cornerstone’s daily consumer confidence survey shows that sentiment has fallen to the lowest level since late 2018. But most of the index’s other factors still suggest otherwise.

As for where markets are heading, Lazar says the index level she and her team estimate for the second quarter historically coincides with the S&P 500 rising 14% over the following four quarters. “Of course, the business cycle is not the only driver of returns, but our RRI does argue against sustained/prolonged stock market weakness,” she said.

Whether the U.S. does fall into recession this year is less important than how quickly and robustly the rebound occurs. Even those with dire near-term projections see growth resuming by the end of the year and into 2021—offering a dose of optimism for investors already hunkering down and living off hoards of non-perishables that, coincidentally, will boost first-quarter GDP and help support full-year GDP.